July

This is a full-on month for pollination, the bees fly every hot, sunny day. The female bee builds cells, packing them with pollen and nectar paste and lays an egg. After hatching the larvae eats this food source then spins a cocoon to begin diapause, the long period of dormancy until the next growing season.

Photo by Mark Higgins

Female bee carefully building a cocoon

Bee on a nearly full block

Larvae inside the cocoons

To be pollinated an alfalfa flower needs its keel opened to expose the pollen-covered stamen. This spring loaded stamen mechanically trips, smacking the bee in the head and allowing the bee to access the pollen. Other types of bees do not like receiving this violent knock on the head by the stamen but leafcutter bees do not mind the discomfort and carry on pollinating.

How an Alfalfa Flower is “Tripped” and Pollinated

A week after release of the bees the incubation trays are collected, empty cocoons are discarded into the field. The incubation trays are washed and stacked ready for next year.

Larvae inside the cocoons

Jody on the pressure washer

Stacks of cleaned incubation trays

August

As the bees fill the nesting tunnels with cocoons they cap the full tunnels with multiple perfectly round pieces of leaf to keeping parasites from getting in.

After a busy 5 to 8 period of flying, pollinating and laying babies the female bees perish. The two generations of bees have a time overlap of only a few weeks.

Female bee sits atop a cocoon

Cocoons made from purple blossoms

After pollination occurs, the alfalfa plants begin to set seed. Curly green seed pods form which then darken upon maturation and contain golden yellow seeds when dry and ripe.

Alfalfa flowers ready to be pollinated

Alfalfa seed pods in varying stages of ripeness

Golden yellow alfalfa seed

September

Grain harvest commences in late August and continues through most of September. Typically we combine lentils first, then wheat, oats and canola, it’s always a relief to have the grain in the bin.

Photo by Mark Higgins

Straight-cutting a wheat crop

Combine empties its load into the truck

Augering grain into the bin

We bring in truckloads of nesting blocks and stack them to dry in our warehouse.

Bringing the nesting blocks in from the field

Kathy stands with two different types of nesting blocks

A stack of very full nesting blocks, spaced apart for drying

October

Alfalfa seed crops are harvested last, often in October. Our combines have modified concaves for extra threshing and need to be finely tuned to do a good job of separating the fine alfalfa seed. Typically by October 31st the ground is frozen bringing fieldwork to an end.

Photo by Gene Pavelich Photography

Notice the wide row spacing of 24 inches as the field is combined

Photo by Mark Higgins

Sunset at the end of the day’s harvesting

Bee hut sits under a starry autumn sky

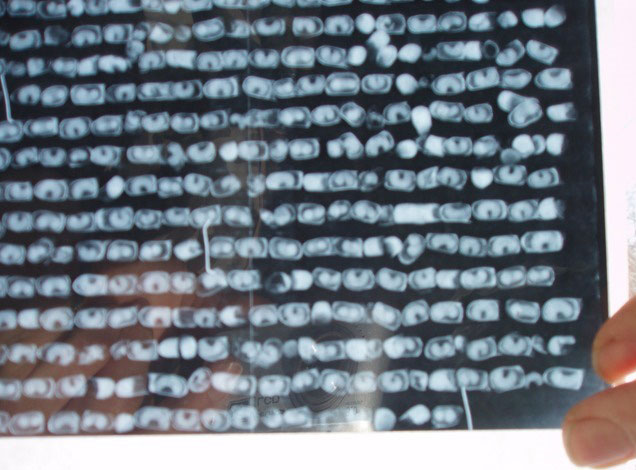

A sample of leafcutter bee larvae can be professionally x-rayed to provide live counts for marketing purposes.

Close-up photo of cocoons

Close-up photo of cocoons

X-ray of bee cocoons done at the Brooks Cocoon Testing Centre.

November

The alfalfa seed gets cleaned, then it is inoculated and bagged, ready for sale in the spring. Our seed gets delivered to customers across Western Canada.

The final product: clean, field-ready alfalfa seed

Work crew at the seed shed

The delivery truck sits under a colorful rainbow

December

Cold weather brings the humidity in the warehouse down and dries out the cocoons inside the nesting blocks. Splitting of the blocks begins when the humidity is below 20%, the nests are split and stacked flat ready for punching.

Humidity meter reading 16%

Cutting the straps off a pair of bee nests

Split nests ready for punching